www.thetinman.org Copyright © All rights reserved.

Disclaimer: The material presented in this site is intended for public educational purposes only. The author is not offering medical or legal advice. Accuracy of information is attempted but not guaranteed. Before undertaking any diet, or health improvement program, you should consult your physician. The author is in no way liable or responsible for any bodily harm, physical, mental or emotional state of any patient reacting to any of the content on this site. Thetinman.org has not examined, reviewed or tested any product or service mentioned herein. We are not being paid to advertise or promote any product or service mentioned herein. The links are offered strictly as examples of resources available. The site assumes no responsibility or liability of any kind related to the content of external sites or the usage of any product or service referenced. Links to external sites were live at the time of creation of the link. Thetinman.org does not create content for or manage external sites. The information can be changed or removed by the external site’s administrators at any time and they are responsible for the veracity of their information. Links are provided to support our data and supply additional resources. Please report broken links to administrator@thetinman.org. Thetinman.org is not a charitable foundation. It neither accepts nor distributes donations or funds of any kind.

Stiff-person syndrome typically develops between the third and fifth decade of life, but has been seen in children, teenagers, and over sixty.

Early detection is critical to delay the progression of the disease. Stiff-person syndrome can be severely disabling, affect life expectancy, and impair physical and mental capabilities. Disability results in reduced quality of life and affects an individual's potential for education and earning. If untreated, SPS can lead to total body rigidity.

The immediate concern upon receiving the diagnosis is how much stiff-person syndrome will interfere with your ability to work, function, perform activities of daily living (walking, eating, dressing), provide for your family, etc.

Chances are, you have been dealing with a level of disability for months or years before you were given the diagnosis. The first thing to consider is that this status is not likely to change quickly.

There should be no immediate worsening and with the right treatment, you can expect the symptoms to level off or even improve.

The first exception would be stiff-person with paraneoplastic syndrome, in which case your symptoms could resolve with the resolution of the cancer.

The second exception is in the case of stiff-person plus PERM which can progress quickly.

According to a study by the National Institutes of Health, “In patients with anti-GAD antibody titers in serum and CSF, the titers do not correlate with disease severity or duration. Anti-GAD antibodies are an excellent marker for SPS, but monitoring their titers during the course of the disease may not be of practical value.”

Classic stiff-person syndrome progresses slowly over years. In some cases, it has stabilized and remained static for decades.

Quality of life varies based on how early the disease is diagnosed and treated and whether there are co-existing autoimmune diseases that complicate the therapeutic picture.

Since the diagnosis is often not reached until patients are in the middle to end stages, it is difficult to calculate progression rates. Few long-term follow-up studies have been done. Careful investigation of patient histories could point to earlier signs and symptoms. A stiff neck is easily dismissed as strain or the result of stress or injury.

Heightened sensitivity, distribution of muscle spasms, sensitivity to stimuli, frequency of falls, events predisposing to falls, and environmental factors that contribute to falls and precipitate spasms such as open spaces, anxiety, crowds, unexpected noises, sudden movement, jarring, approaching cars, a sense of hurry or emotional upset can be measured by the National Institutes of Health Sensitivity Scale with a maximum score of 7.

There is much debate about identifiable stages and the progressive nature of the disease. However, the following stages were suggested by Drs. S. Hadavi, AJ Noyce, RD Leslie, and G Giovannoni:

EARLY STAGE

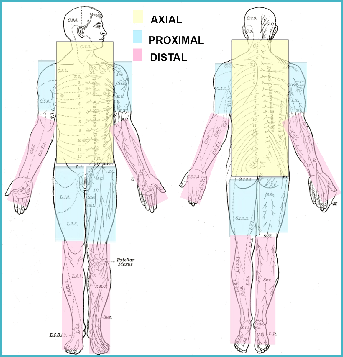

The disease begins insidiously in the axial muscles. In a few cases, the symptoms developed over weeks, though the general theory is over months and years. The patient may complain of neck and/or back pain and stiffness which is worse with tension, overexertion, or stress. They may have an exaggerated upright posture. Symptoms are usually relieved by deep sleep, but during the transition from REM cycles to stage 1 or 2, spasms may awaken them. Patients may report periods of worsening symptoms that resolve spontaneously over hours or days.

ADVANCED STAGE

The second phase involves the proximal limb muscles. Patients experience startle responses to surprise, anger, fright, unexpected noises, etc. and severe spasms that resolve slowly. Rapid movement can induce severe spasms. Distal extremities can become involved. If abdominal muscles contract, the patient can develop lumbar hyperlordosis. If chest muscles contract, the patient can develop kyphosis. Depression becomes a factor as the patient’s quality of life declines. It can become difficult, eventually impossible, to drive, work, shop, go on social outings, and navigate outdoor areas or changes in surfaces.

END STAGE

The disease accelerates to involve the majority of muscles, including paraspinal, chest, abdominal, facial, and pharyngeal. Limbs can become contracted. Spasms can be severe enough to cause bone fractures and muscle ruptures. Abdominal incisions are at risk of spontaneous rupture. Respiratory and gastrointestinal functions can be compromised. Esophageal spasms and obstruction are possible.

Activities of daily living require assistance: walking, climbing stairs, cooking, managing medications, and operating electrical devices, eating, bathing, dressing, grooming, oral care, and transfers from bed to standing, chair, toilet, etc.

In seven reported cases, patients died suddenly and unexpectedly. Some were attributed to respiratory problems that were clinically manifested by sudden apnea with cyanosis, tachypnea, and respiratory arrest which may be caused by diaphragmatic spasms, impaired respiratory function, and severe respiratory muscle rigidity.

Every patient is unique. Several have experienced remissions, sometimes for years. A flare can occur during times of high stress, injury, or physical overexertion. A period of complete rest can result in periods of relief.

Patients presenting with stiff-person syndrome with PERM and paraneoplastic variants have a higher rate of mortality. Co-existing diseases affect the overall health of the patient and affect the outcome.

PROGRESSION AND STAGES

NIH SENSITIVITY SCALE

1 Spasms induced by noise

2 Spasms induced by visual stimuli

3 Spasms induced by somatosensory stimuli (light touch)

4 Spasms induced by voluntary activities

5 Spasms induced by stress or emotional upset

6 Spasms untriggered

7 Spasms induced when awakened or nocturnal spasms.

NIH STIFFNESS SCALE

0 No stiff areas

1 Stiffness of the lower trunk

2 Stiffness of the upper trunk

3 Stiffness of both legs

4 Stiffness of both arms

5 Stiffness of the face

6 Stiffness of the abdomen and back

TIMED ACTIVITIES

1. Rising from a chair

2. Walking a 30 foot length of corridor

3 .Turning 180 degrees with feet together, clockwise and counter clockwise.

4. Going up and down a regular flight of stairs